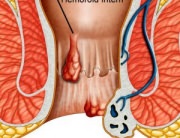

Haemorrhoids arise from congestion of internal and/or external venous congestion around the anal canal. Depending on their severity, haemorrhoids are classified into four groups.

The first group comprises haemorrhoids that bleed but do not prolapse outside of the anal canal; the second group comprises haemorrhoids that prolapse outside of the anal canal, usually upon defecation, but retract spontaneously. The haemorrhoids in the third group require

the manual introduction in the anal canal after prolapse and the fourth group comprises haemorrhoids that cannot be manually inserted and are generally throttled or thrombosed.

Symptoms associated to haemorrhoids include pain, bleeding, anal pruritus (itching) and mucus elimination. In the fourth group of haemorrhoids, the area where the rectal mucous membrane joins the anal skin (dentate line) is located outside the anal canal, and the rectal membrane permanently occupies the muscle anal canal.

Traditional Surgery in the Treatment of Haemorrhoids:

In some cases, the haemorrhoidal disease can be treated by changing the diet, the typical medication and with sitz baths that temporarily relieve pain and swelling. In addition, non-surgical treatment methods are available for most patients as a viable alternative to a permanent haemorrhoid cure.

In a certain percentage of cases, however, surgical procedures are necessary to provide satisfactory, long-term relief. In cases involving a greater degree of prolapse, a variety of operative techniques are employed to address the problem.

Milligan-Morgan Technique

Developed in the United Kingdom by Drs. Milligan and Morgan, in 1937. The three major haemorrhoidal vessels are excised. In order to avoid stenosis, three pear-shaped incisions are left open, separated by bridges of skin and mucosa. This technique is the most popular method, and is considered the gold standard by which most other surgical haemorrhoidectomy techniques are compared.

Ferguson Technique

Developed in the United States by Dr. Ferguson, in 1952. This is a modification of the Milligan-Morgan technique (above), whereby the incisions are totally or partially closed with absorbable running suture. A retractor is used to expose the haemorrhoidal tissue, which is then removed surgically. The remaining tissue is either sutured or is sealed through the coagulation effects of a surgical device.

Due to the high rate of suture breakage at bowel movement, the Ferguson technique brings no advantages in terms of wound healing (5-6 weeks), pain, or postoperative morbidity.

Conventional haemorrhoidectomy can be performed as a day-case procedure. But due to poor post-operative care in the community and high level of pain experienced after the procedure, an in-patient stay is often required (average of 3 days).

Stapled Haemorrhoidopexy (PPH Procedure) in the Treatment of the Haemorrhoidal Disease:

Also known as Procedure for Prolapse & Haemorrhoids (PPH), Stapled Haemorrhoidectomy, and Circumferential Mucosectomy.

PPH is a technique developed in the early 90’s that reduces the prolapse of haemorrhoidal tissue by excising a band of the prolapsed anal mucosa membrane with the use of a circular stapling device. In PPH, the prolapsed tissue is pulled into a device that allows the excess tissue to be removed while the remaining haemorrhoidal tissue is stapled. This restores the haemorrhoidal tissue back to its original anatomical position.

The introduction of the Circular Anal Dilator causes the reduction of the prolapse of the anal skin and parts of the anal mucous membrane. After removing the obturator, the prolapsed mucous membrane falls into the lumen of the dilator. The anoscope is then introduced through the dilator.

This anoscope will push the mucous prolapse back against the rectal wall along a 270° circumference, while the mucous membrane that protrudes through the anoscope window can be easily contained in a suture that includes only the mucous membrane. By rotating the anoscope, it will be possible to complete a purse-string suture around the entire anal circumference. The Haemorrhoidal Circular Stapler is opened to its maximum position. Its head is introduced and positioned proximal to the purse-string, which is then tied with a closing knot.

The ends of the suture are knotted externally. Then the entire casing of the stapling device is introduced into the anal canal. During the introduction, it is advisable to partially tighten the stapler.

With moderate traction, a simple manoeuvre draws the prolapsed mucous membrane into the casing of the circular stapling device. The instrument is then tightened and fired to staple the prolapse. Keeping the stapling device in the closed position for approximately 30 seconds before firing and approximately 20 seconds after firing acts as a tamponade, which may help promote hemostasis.

Firing the stapler releases a double staggered row of titanium staples through the tissue. A circular knife excises the redundant tissue. A circumferential column of mucosa is removed from the upper anal canal. Finally, the staple line is examined using the anoscope. If bleeding from the staple line occurs, additional absorbable sutures may be placed.

What are the Benefits of PPH over other Surgical Procedures?

- Patients experience less pain as compared to conventional techniques.

- Patients experience a quicker return to normal activities compared to those treated with conventional techniques.

- Mean inpatient stay was lower compared to patients treated with conventional techniques.

What are the Risks of PPH?

Although rare, there are risks that accompany PPH:

- ● if too much muscle tissue is drawn into the device, it can result in damage to the rectal wall.

- ● the internal muscles of the sphincter may stretch, resulting in short-term or long-term dysfunction.

- ● as with other surgical treatments for haemorrhoids, cases of pelvic sepsis have been reported following stapled haemorrhoidectomy.

- ● PPH may be unsuccessful in patients with large confluent haemorrhoids. Gaining access to the anal canal can be difficult and the tissue may be too bulky to be incorporated into the housing of the stapling device.

- ● persistent pain and fecal urgency after stapled haemorrhoidectomy, although rare, has been reported.

- ● stapling of haemorrhoids is associated with a higher risk of recurrence and prolapse than conventional haemorrhoid removal surgery; according to a Canadian study of 537 participants.